In 1866, amidst the dangers of Native American tribes, Nelson Story boldly drove a herd of Texas longhorn cattle along the perilous Bozeman Trail. This act of pioneering spirit laid the foundation for Montana’s thriving cattle industry. His arduous journey and visionary foresight are etched in history, making Montana’s oldest ranches symbols of resilience and prosperity.

Early Ventures and a Dream of the West

Nelson Story was born in Ohio in 1838, growing up on a farm. Despite attending Ohio University, he left academia to forge his own path. At 20, Story began his career teaching, then headed West in search of opportunity. He tried various ventures in Illinois, Nebraska, and Kansas, from freighting to gold mining. In 1859, Story sought gold in Montana but was unsuccessful, returning to Kansas to continue trading.

The turning point came in 1862 when a lumber hauling contract took Story to Missouri, where he met and married Ellen Trent. In spring 1863, the young couple ventured to Bannack, Montana, bringing goods to open a store for miners. Arriving, they discovered the gold rush had shifted to Alder Gulch. Undeterred, Story and Ellen continued to Virginia City, setting up a small shop. Ellen baked bread and pastries for miners, while Nelson managed the store, hauled goods, and mined gold in Alder Gulch.

Through hard work and acumen, the Storys’ business flourished. They acquired mines and expanded operations in 1865, employing 50 men day and night. By 1866, they had accumulated significant capital from gold. However, Nelson Story saw greater potential in supplying beef to Montana’s growing mining market. The audacious idea to bring Texas longhorns to Montana was born, marking a new chapter for him and Montana’s cattle industry history.

The Legendary Journey Across the Bozeman Trail

With his savings, Nelson Story resolved to execute a daring plan: drive a herd of Texas longhorn cattle to Montana to supply beef to miners. He believed the demand for beef in mining areas would yield enormous profits. In 1866, Story and two friends from Kansas hired 21 cowboys in Texas to help drive nearly 3,000 longhorns. The group and livestock began their arduous journey that spring.

They crossed the Red River into Oklahoma, then followed the Neosho River to the Kansas border. The journey was far from smooth. Eastern Kansas farmers, fearing Texas cattle would ruin crops and spread disease, vehemently protested. The Greenwood County Sheriff even arrested Story, fined him, and ordered him to remove his herd from the county.

Undaunted, Story redirected his herd westward, eventually reaching Leavenworth. There, he better prepared for the journey ahead, purchasing wagons, oxen, supplies, and crucially, 30 Remington rifles for his men. News of a “Native American uprising” in the North was spreading, heightening Story’s awareness of the dangers ahead. Remington rifles, with their rapid reloading and firepower, became vital equipment.

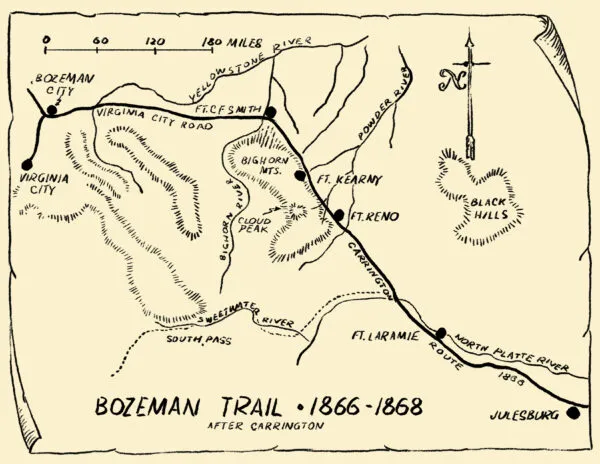

By July, Story’s cattle crossed Nebraska and followed the South Platte River to Julesburg, Colorado, where a new trail north led to Montana – the Bozeman Trail. At Fort Laramie, army officers warned Story of the tense situation with Native Americans.

The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty between the U.S. and eight Northern Plains tribes recognized Native American sovereignty and defined tribal territories. However, the Pike’s Peak gold rush in 1858 and the Bozeman Trail’s opening in 1863, drawing thousands of migrants into Cheyenne and Lakota territory, quickly violated this treaty. This encroachment disrupted Native American life, affected buffalo migration, and sparked conflict. The 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, where the army slaughtered a peaceful Cheyenne village, further escalated tensions. In 1866, the U.S. Army began building three forts along the Bozeman Trail to protect settlers, further angering Native American tribes.

Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes allied, determined to drive whites from their territory. They focused on attacking soldiers, travelers, and raiding livestock, hoping to lure the army into ambushes.

Story’s herd first encountered Native Americans in early October near Fort Reno. Continuous attacks ensued, causing livestock and human losses. However, thanks to rapid-firing rifles, Story’s cowboys repelled the attacks. In one fierce encounter, Story reportedly strapped two revolvers to his hands, riding bareback to defend his herd. He and two cowboys were once lured into a trap but recognized it and retreated in time.

On October 7th, Colonel Carrington ordered Story to halt near Fort Phil Kearny, warning that continuing was too dangerous. However, Story feared the army would undervalue his cattle, so he decided to press on. Defying orders and imminent danger, Story resolutely led his herd across the Bozeman Trail at night, avoiding army control. He moved cattle at night and rested during the day, enduring two more attacks but successfully fending them off.

Finally, in December 1866, Nelson Story’s herd reached Montana, crossing the Yellowstone River and entering the Gallatin Valley. He completed a journey many consider the longest and most perilous in cattle driving history.

The Bozeman Trail and surrounding areas where most of Nelson Story’s cattle drive took place. (Photo: Junhao Su for American Essence)

Foundation of Montana’s Cattle Industry

On December 9, 1866, Story’s first cattle and wagons arrived in Virginia City. Beef was scarce, prices ten times Story’s initial cost. The risky journey was a resounding financial success.

Meanwhile, at Fort Phil Kearny, just days after Story left, the Fetterman Massacre occurred. On December 21st, Native Americans ambushed and annihilated a detachment led by Captain William J. Fetterman, killing all 81 men. This disaster ended government efforts to protect the Bozeman Trail. In 1868, Chief Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota signed a peace treaty, reclaiming sovereignty over the Powder River Country. Forts along the Bozeman Trail were abandoned and burned.

After selling his cattle, Nelson Story became one of Virginia City’s wealthiest citizens. Over the next two decades, he built a massive cattle ranch with 15,000 head in Paradise Valley, near Bozeman. His ranch became one of Montana’s oldest and a cornerstone of the state’s cattle industry development.

Nelson Story’s Legacy

Story soon moved to Bozeman and invested in various businesses, from flour mills and banks to real estate. He became one of the city’s largest employers. His three-story mansion was a landmark, often mistaken for the courthouse. Story contributed significantly to Bozeman, notably donating land to establish Montana State University. He also entered politics, serving as Bozeman’s mayor and Lieutenant Governor of Montana.

However, Nelson Story was a complex, imperfect figure. He faced accusations of fraud in dealings with the Crow Reservation. His temper and use of force were also noted.

Yet, Nelson Story’s pioneering role and impact on Montana are undeniable. He laid the foundation for the state’s cattle industry, significantly contributing to Montana’s economic and social development. Catlin’s quote about Story perhaps best summarizes him: “Story always rode magnificently and fast as the wind… He would say ‘Hurry up boys,’ and ride off. Of course, we would have to follow him… The Indians knew Story very well. They also feared him. For they knew that he would go through anything to accomplish what he started out to do.”

Nelson Story’s journey and Montana’s oldest ranches exemplify the pioneering spirit, perseverance, and vision of the Western frontier. His legacy lives on in Montana’s history and culture.