Alaska, a vast and wild land, is not only famous for its magnificent natural beauty but also hides a turbulent and painful military history. From conflicts between the Russian Empire and indigenous peoples like the Chukchi, Aleut, and Tlingit, to bloody battles and brutal policies, the history of warfare in Alaska is an inseparable part of this land. This article will take readers on a deeper exploration of Alaska’s military history, from mysterious “curses” to genocidal tragedies, revealing a lesser-known aspect of this region.

The story of the Russian Tsar selling Alaska to the United States is always a controversial topic with many different theories. Besides the familiar reasons such as fear of losing Alaska to Britain, a lesser-known but equally important perspective stems from the internal affairs of the Russian Empire itself. That was Russia’s inability to completely conquer the Chukchi Peninsula, the land connecting Siberia and Alaska. The Russian Empire feared that the Chukchi people’s fierce resistance would hinder the deployment of troops to Alaska if war broke out. Even the Russians themselves admitted defeat in subjugating the Chukchi people, and from there, stories of the “Chukchi curse” were born, haunting Russia’s conquests in this land.

The Chukchi Curse: When the Russian Empire Fell Before Indigenous Power

Battle of Yegach (1730): The Beginning of the “Curse”

In the early 18th century, the Russian Empire had almost completed the conquest of Siberia, imposing dominion over many peoples and even wiping out some tribes. However, one last formidable opponent remained: the Chukchi people, living in northeastern Siberia, near Alaska. In 1729, to subdue the Chukchi, the Russian Tsar sent General Afanasy Shestakov to lead a Cossack army to the Chukchi Peninsula.

Shestakov commanded 400 Cossack soldiers along with auxiliary troops from conquered peoples such as Tatars, Yakuts, and Samoyeds. Marching in harsh conditions, lacking information about the terrain and the enemy, Shestakov’s force gradually increased to about 1,000 men by conscripting soldiers from indigenous peoples along the way. By 1730, the Russian army reached the Yegach River, the border of Chukchi territory. Here, they recruited more soldiers from neighboring peoples of the Chukchi, such as the Koryak, Even, and some Kamchatka tribes. These peoples had tense relations with the Chukchi, often being attacked and suffering losses. They saw the appearance of the Russian army as an opportunity to counter the Chukchi expansion.

On March 14, 1730, the Russian army crossed the frozen Yegach River, dividing into three wings to attack the Chukchi. The Northern wing consisted of Koryaks, the Southern wing was Even, and the central wing was commanded by Shestakov with 144 Cossack soldiers, supported by Yakut troops behind. The Russian army also had reindeer sleds, hoping to gain an advantage over the Chukchi.

However, the Chukchi had made careful preparations. The night before the battle, they unexpectedly attacked the Koryak wing, causing a terrible massacre. The Koryak, already terrified of the Chukchi’s power, quickly collapsed and fled. At dawn, the Chukchi greeted the Cossack soldiers with a rain of bone arrows. Although they could not penetrate armor, these arrows caused fatal wounds. The Russian soldiers did not have time to reload, and the Koryak and Even wings fled, leaving the Cossack soldiers with a small force.

General Shestakov was forced to rush forward, leading the remaining 30 Cossack soldiers in direct combat. The skills and weapons of the Russian army were superior, with rifles and sharp swords compared to the spears and bone arrows of the Chukchi. But in the midst of the battle, Shestakov was suddenly hit by a bone arrow in the throat. He tried to escape but was dragged by a reindeer sled straight into the Chukchi formation. As a result, General Shestakov died tragically under a barrage of arrows and spears from the enemy.

All Russian soldiers were subsequently killed, with only one interpreter spared to report the news. The Russian army retreated, suffering heavy losses with 31 Cossack soldiers killed, while most auxiliary troops fled. The Chukchi captured many spoils of war, including gunpowder, animal skins, Russian rifles, and armor. After the battle, stories of the “Chukchi curse” began to spread, claiming that the souls of the fallen Russian soldiers were cursed by Chukchi shamans. The Battle of Yegach was the Russian army’s heaviest defeat against an indigenous Siberian people, and it also ignited the spirit of resistance among the Koryak and Itelmen peoples.

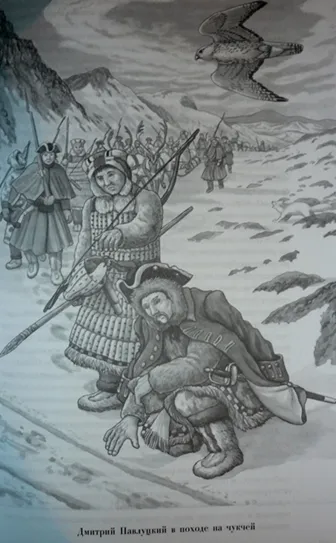

Dmitry Pavlutsky’s Bloody Revenge

After the defeat at Yegach, the Russian Tsar sent General Dmitry Pavlutsky to suppress the uprisings and take revenge on the Chukchi. From 1731, Pavlutsky continuously attacked the Chukchi, causing heavy damage. The Cossack army under Pavlutsky was known for its brutality, implementing genocidal measures against indigenous peoples who refused to submit.

In 1742, Empress Elizabeth issued a decree “Annihilate the Chukchi!”, legalizing the brutal actions of the Russian army. Russian soldiers burned villages, killed livestock, massacred men, captured women and children, raped…, causing horrific crimes that severely reduced the indigenous population of Siberia. The image of “Yakunin the Devil,” a monster destroying Chukchi villages in 19th-century folklore, is believed to personify General Pavlutsky.

During this time, the Chukchi also faced epidemics, especially smallpox and syphilis, which they called “Russian Disease” (Русская болезнь). The Chukchi population declined sharply due to war and disease. To consolidate military control, Pavlutsky built Anadyrsk Fortress, serving as both a military base and a place to collect taxes (yasak) from the natives. This fortress was also known as “Anadyrsk Great Prison” because it was used to detain prisoners.

Battle of Orlova (1747): Pavlutsky’s Death and Russian Retreat

However, Pavlutsky’s brutality did not subdue the Chukchi but instead made them even more determined to resist. In 1747, the Chukchi launched a strong counterattack, brutally retaliating against peoples who collaborated with Russia. The Koryak and Even were continuously attacked. In March 1747, the Koryak appealed to Pavlutsky for help when they were attacked by the Chukchi near Anadyrsk Fortress. Pavlutsky discovered about 500 Chukchi soldiers stationed at the mouth of the Orlova River, near the fortress.

On March 12, 1747, Pavlutsky led more than 200 Cossack and auxiliary troops to the Orlova River, facing 500 Chukchi soldiers. Despite advice to attack immediately, Pavlutsky hesitated, waiting for reinforcements and building fortifications. Two days later, the battle broke out, exactly on March 14, the day General Shestakov died 17 years earlier.

The Battle of Orlova unfolded similarly to the Battle of Yegach. The Chukchi attacked with a rain of bone arrows, causing heavy losses to the Russian army. Despite iron armor protection, other parts of the Russian soldiers’ bodies were still seriously wounded. The Chukchi army, twice as large, quickly overwhelmed the Cossack soldiers. Pavlutsky fought bravely but was surrounded, overwhelmed, and killed by the Chukchi. According to legend, Pavlutsky removed his armor to accept a brave death. The Chukchi then kept Pavlutsky’s head for use in rituals.

The Russian army retreated, suffering heavy losses with 51 dead, losing a cannon, 40 rifles, and many other spoils of war. This was a Pyrrhic victory for the Chukchi, as they also suffered heavy losses.

Aftermath and the “Chukchi Curse”

After the Battle of Orlova, the Russians realized the strange coincidence: the two generals commanding Russia’s conquest of the Far East both died on March 14, 17 years apart. Coupled with rumors about the Chukchi cursing fallen Russian soldiers, the “Chukchi curse” spread even wider.

The Chukchi actually used the bodies of Russian soldiers, especially General Pavlutsky’s head, in their shamanistic rituals. They believed that keeping Pavlutsky’s head would bring them the courage of the Russian general.

The “Chukchi curse” discouraged the Russians from conquering this land. From then on, Russia shifted to a peaceful policy with the Chukchi. After 1747, there were no more major Russian attacks on the Chukchi. Empress Elizabeth ordered the withdrawal of troops, destroyed Anadyrsk Fortress, allowing the Chukchi to live in peace. The Chukchi became the only people to repel the invasion of the Russian Empire.

By 1870, the “Chukchi curse” was mentioned again when a Chukchi leader returned Pavlutsky’s head to the Russian police chief. At this time, the Chukchi had integrated into Russia, becoming an Autonomous Okrug under Soviet rule.

Battle of Sitka (1804): Massacre of the Tlingit and the End of the “Mourning Ceremony”

On the southeastern coast of Alaska lived the Tlingit people. Previously, the Tlingit had a “Mourning Ceremony” to commemorate ancestors killed by Russian soldiers and forced into remote lands for 200 years. This two-century-long festival ended in 2004, closing a painful chapter in Tlingit history.

Context of Invasion and Tlingit Resistance

The exploration of Alaska for Russia is associated with the name Alexander Baranov. From 1795, Baranov explored the islands off the coast of Alaska, turning the Aleut into vassals. He then led Russians and Aleuts to land on the Alaskan mainland. Initially, they bought land from the Tlingit, but later, realizing the backwardness of the natives, the Russians began to encroach, seize land, and enslave the Tlingit. In 1799, Russia built Mikhailovskaya Fortress, suppressing the Tlingit.

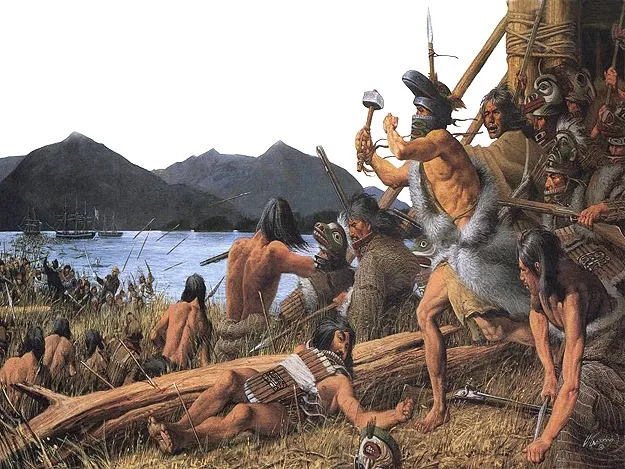

In 1802, Tlingit tribes allied to attack Mikhailovskaya Fortress, killing many Russian and Aleut soldiers and taking hostages. After Russia paid the ransom, Baranov was determined to retaliate. For two years, he prepared troops, built ships, conscripted auxiliary soldiers, ready to destroy the Tlingit.

Battle of Sitka (1804): Bloodshed on Tlingit Land

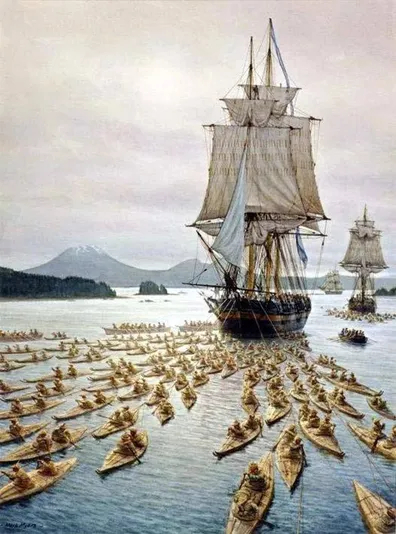

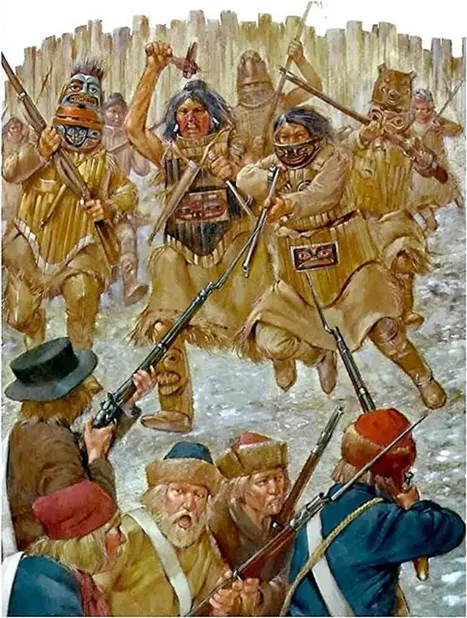

The Tlingit knew of Russia’s intentions and built Shís’gi Noow Fortress (present-day Sitka) for defense. Russia sent a powerful force, including the warship “Neva” (14 cannons), 400 Eskimo and Aleut kayaks, totaling nearly 200 Russian soldiers and over 1000 auxiliary soldiers, under the command of Admiral Yuri Lisyansky.

The Tlingit fortress was deep in the river, inaccessible to the “Neva”. The Russian army used hundreds of kayaks to tow the “Neva” into the river. On October 1, 1804, Baranov landed at the fortress but was ambushed, wounded, and had to retreat. The “Neva” fired in support, and the Russian army withdrew, suffering losses of 12 Russian soldiers and several dozen Aleut soldiers. The initial victory boosted the morale of the Tlingit.

With Baranov wounded, Lisyansky took command. He ordered the “Neva” to bombard the fortress continuously. When the fortress remained solid, Lisyansky changed tactics, raising the cannons to fire in an arc into the interior. This tactic was effective, terrifying the Tlingit.

On October 4, 1804, the Tlingit began to evacuate, prioritizing women and children. When the Russian army landed, the Tlingit leaders surrendered, promising to hand over the fortress. On the evening of October 4, Tlingit elders and warriors held a final ceremony, erecting steles, praying, commemorating the deceased, ending with drums and mournful cries. The Russian army thought it was a sign of surrender and advanced to occupy the fortress. The Tlingit withdrew. From then on, the “Mourning Ceremony” was born, commemorating the pain and loss.

Aftermath and Genocidal Tragedy

After the Battle of Sitka, the Russians forced the Tlingit into remote areas, causing them to live in misery, lose land, and suffer population decline due to hunger, cold, disease, and massacres. The peak was the smallpox epidemic in 1862, which claimed the lives of 60% of the Tlingit population. Russia’s weak healthcare system also contributed to this disaster. This is one of the reasons Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867. The Tlingit lost more than 93% of their population, from 100,000 to under 10,000 by the early 20th century. Other tribes like the Aleut also suffered the same fate.

The horrific memories of the Russian invasion still haunt the indigenous people of Alaska. In 2020, the statue of Alexander Baranov was destroyed by supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement, considering him a symbol of genocidal crimes.

Russian-Aleut War (1763-1765): The Beginning of a Nation’s Destruction

The Aleutian Islands, a bridge between Asia and America, are the homeland of the Aleut people, the only people whose territory is in both continents. However, the fate of the Aleut people is also a typical tragedy for the indigenous peoples of America. From the 18th century to 1910, the Aleut lost 95% of their population, from 25,000 to 1,491 people. The main causes were the Russian invasion, disease, forced migration, discrimination, and World War II. The Russian-Aleut War (1763-1765) was the beginning of this tragedy.

Background and the 1763 Uprising

In 1741, Vitus Bering discovered Alaska for Russia. In 1762, Stepan Glotov discovered the Aleutian Islands, inhabited by the Aleut people and rich in fur resources. Russian traders flocked in, forcing the Aleut to pay yasak tax in furs. Initially, the Aleut agreed, in exchange for money and goods. But later, Russian traders became increasingly exploitative, looting, and kidnapping Aleut people.

In 1763, the Aleut in the Fox Islands rose up, triggered by the trader Ivan Bechevin beating and robbing the son of an Aleut leader. The Aleut attacked Russian merchant ships. At the end of December 1763, they burned 3 Russian ships, killing all the sailors. A group of 13 sailors escaped, surviving thanks to the leadership of Korovin. The ship “St. Nicholas” retaliated, destroying 4 Aleut villages, but was defeated and burned.

In August 1764, Korovin’s group contacted Stepan Glotov’s ship. Glotov was furious and determined to destroy the rebellious Aleut.

War and Massacre (1764-1765)

Stepan Glotov led a small fleet (2 ships) to suppress the Aleut. The Russian fleet had large cannons and skilled sailors, easily massacring the Aleut. Ivan Soloviev, commander of one of the two ships, was described as a brutal man, mainly responsible for the massacre of thousands of Aleut people. Soloviev killed all the villagers in the southern part of Unmak Island, sparing no women or children. Russian officer Gabriel Davydov estimated that Soloviev killed more than 3,000 Aleut people on Unmak Island in 1764. Navy Minister Gavriil Sarychev believed that no fewer than 5,000 Aleut died at the hands of Soloviev. The Aleut population decreased 3 to 5 times during the 1764-1765 war.

After 1765, the Aleut lost their independence, becoming vassals of Russia, exploited in other invasions in Alaska.

Policy Changes and Belated Reconciliation

The Russian government realized that the brutality of Russian traders was harming yasak tax revenue and decided to protect the Aleut with laws. However, this policy did not become truly effective until the 1800s thanks to “humanitarian Naval officers”.

Russian officers and missionaries from the 1800s had a more humanitarian attitude, providing medical care, missionary work, and scientific research about Alaska. They acknowledged the crimes of earlier Russian traders. Lieutenant Gabriel Davydov, Minister Gavriil Sarychev, and missionary Ivan Veniaminov were typical examples, recording the brutality of the Russian army and contributing to the protection of indigenous peoples. Even though Alaska belonged to the United States, these Russians are still revered by the natives and honored with the names of islands.

Conclusion

The history of war and military affairs in Alaska is a complex and painful picture. From the “Chukchi curse” to the Sitka tragedy and the destruction of the Aleut, these conflicts not only shaped Alaska’s history but also left deep scars in the hearts of indigenous peoples. However, alongside the dark pages of history, there are also stories of steadfast resistance, bravery, and belated policy changes. Exploring Alaska’s military history helps us better understand the turbulent past of this region and appreciate the diverse cultural and historical values here. Alaska is not only an attractive tourist destination with magnificent nature, but also a living history museum where visitors can learn about the intersection of cultures, fierce wars, and profound humanistic lessons.